Illustration by Lauren Halligan, CMI, Department of Surgery

After hearing a lecture on posture in the operating room (OR), all six of last year’s chief residents in General Surgery suddenly understood the cause of their persistent lower neck pain. The loupes they used to magnify and visualize the operative field did not fit properly, and this improper fit forced them to bend their necks at an awkward angle during long hours in surgery. Over years of training, the seemingly small error in fit had led to noticeable health issues.

“As residents, we spend so much time focusing on learning about disease processes and anatomy, how to get through a case, and surgical technique, that posture is probably the last thing anybody worries about,” says Dr. Michael Lidsky, recent graduate of the Duke General Surgery Residency. “But, poor posture is probably one of the most detrimental things to a surgeon’s career, and can result in major injury.”

Ergonomic stressors in the OR, such as maintaining awkward positions for extended periods of time, can lead to a variety of musculoskeletal problems. Surgeons often develop pain in their neck, shoulders, and back, which may become debilitating, forcing them to halt an operation or miss work entirely. If left unchecked over time, significant degenerative changes can manifest, possibly resulting in a career-ending injury.

“We know that our senior surgeons have had health issues before,” says Dr. Georgios Kokosis, another recent graduate of the General Surgery Residency. “It’s something that we don’t really pay much attention to, but it does have clinical implications. Unless we find ways to prevent it in the future, it will be happening to generations of surgeons.”

Ergonomics in the Operating Room

In collaboration with the Duke Ergonomics Division and with support from Department of Surgery Chair Dr. Allan Kirk, several General Surgery residents initiated a program to teach junior residents and medical students about proper positioning in the OR. The program includes an ergonomic loupe fitting initiative currently in development, ergonomics labs with residents, one-on-one observation of the chief residents, and coach training for the rising chief residents.

“Surgeon positioning should be a high priority in the OR,” says Marissa Pentico, ergonomics coordinator. “The ergonomics team identifies ergonomic risk factors when assessing general work tasks, including awkward postures and prolonged duration of tasks performed. The General Surgery residents are in surgery between 5 and 8 hours, so we make recommendations that will address those risk factors.”

According to Ms. Pentico, these recommendations include avoiding awkward postures when performing surgery by adjusting the height and position of the patient and the operating table, alternating postures by sitting when feasible depending on the type of case, and selecting the most ergonomic equipment to use.

“Certain instruments, if you use them a lot during a case, just the way you hold them in your hands, they’re not ergonomically optimized and it’s a one size fits all,” explains Dr. Lidsky. “What fits a 6 foot 5 male surgeon isn’t necessarily the best device for a 5 foot 3 female surgeon. A lot of that is industry-based.”

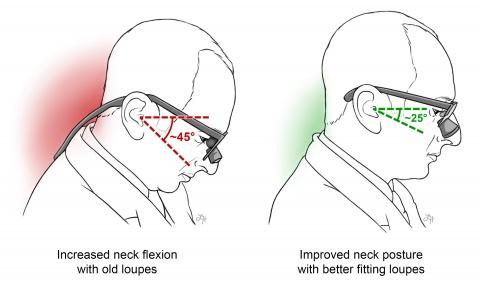

As part of the program, each resident is fitted with loupes that sit at a proper declination angle to minimize neck flexion. Maintaining neck flexion at less than or equal to 25 degrees can prevent spine and neck strain during long stints in the OR. Additionally, the ergonomics team suggests that residents use anti-fatigue mats and take microbreaks for stretches to reduce the risk of injury.

Peer-Based Ergonomics Training

The Duke Surgery ergonomics program is uniquely peer-based and thus fosters collaborative learning. The program aims to have fifth-year General Surgery residents act as ergonomics “coaches” to train junior residents on correct postures during surgery. To ensure the continuation of the program, each year before they graduate, the chief residents will train rising chief residents to be the next group of coaches.

“In addition to teaching surgical technique to junior residents and to each other, senior residents will also be cognizant of their own posture and the way they stand, the way they hold their hands, and the way they have their loupes fitted,” says Dr. Lidsky. “A lot of this is to promote good patterns, better posture, and improved technique early on, which is much easier than taking people like us who have spent a number of years in less optimal positions. It’s harder to change it that way.”

Early intervention is exactly what research resident Dr. Shanna Sprinkle hopes to do by targeting medical students before they form bad postural habits. Medical students spend a lot of time practicing their skills independently or at home without an instructor to observe and verbally correct them, explains Dr. Sprinkle.

“When we surveyed some of our medical students, 78% of them rated their posture during surgical tasks as poor or very poor,” says Dr. Sprinkle. “What’s alarming though is that more than half of them say they regularly experience musculoskeletal pain while performing surgical skills.”

Dr. Sprinkle and other residents in Duke’s Surgical Education Research Group (SERG) conducted a pilot study in which medical students practiced a suturing task multiple times while wearing a small device that attached to their shirt and sensed when they started to slouch. After measuring their baseline postures, half of the students then had their device set to vibrate every time they slouched. The other half were told that the device was continuously evaluating their posture. Both groups improved their posture at first, but the group that experienced the vibratory feedback maintained the correct posture 76% of the time, even after the vibrations were turned off, compared to only 42% of the time for the group that did not receive the feedback.

Dr. Sprinkle will present the results of the study at the Association of Surgical Educators conference in April.

“Ergonomics relies on establishing good habits early on,” says Dr. Cecilia Ong, one of the co-authors on the project and another Duke General Surgery research resident. “These wearable devices provide continual feedback that can promote the development of good habits and their continual reinforcement throughout training.”

Countering the Surgeon Culture

A recent study in the Journal of the American College of Surgeons found that of 127 surgical oncologists surveyed, 90% experienced at least one symptom of ergonomic injury, and 28% reported an ergonomic injury or chronic condition. While guidelines for surgical ergonomics exist, a lack of awareness persists among the surgical community.

Coupled with this nescience is a culture that prizes resilience under stressful situations, often conditioning residents to “work through the pain.” However, this mentality backfires when untreated injuries lead to major health problems later on in a surgeon’s career. A new focus on improving surgeon health with ergonomic training programs and interventions, such as wearable devices, will ultimately enhance surgeon longevity.

“I think this is part of the surgeon’s culture that we don’t really focus on,” explains Dr. Kokosis. “We’re focused more on being great at what we do, but we don’t really focus on the appropriate posture. As long as we can start talking about it more and come up with ways to prevent it from happening, I think it will be a great start of a program that we hope will be our legacy.”