This piece is part of a series featuring Black voices from the surgical and emergency medicine communities at Duke.

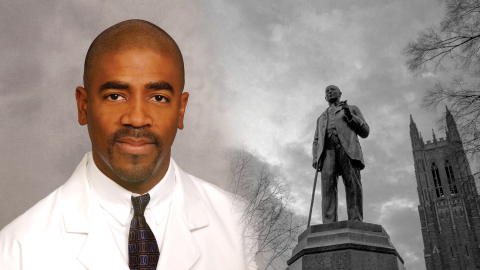

About Dr. Bradley Collins

Dr. Collins attended Duke University for medical school and completed his residency and research fellowship at Duke. After a surgery fellowship at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, Dr. Collins returned to Duke where he has been a faculty member since 1999.

Q: Could you describe your personal reasons for pursuing a career in healthcare? Was race at all influential in that decision?

Race didn't influence my decision to enter healthcare, but television did. When I was 12 or 13, I was hooked on the TV show, Emergency! It was a drama that followed the activities of paramedics in Los Angeles. Their jobs looked fun, so I decided that I wanted to be an EMT. A couple of years later, the show Trapper John, M.D. became my favorite. It was based on two former Army surgeons, one from the Korean War and the other from the Vietnam era, who worked at a hospital in San Francisco. The storyline was boring by today's standards, but after a couple of episodes, I decided that I wanted to be a surgeon.

The transplant part came completely by chance—one Sunday I happened upon a random magazine on our kitchen table with a man on the cover I had never heard of: Dr. Thomas Starzl. I read the article and learned that he was a transplant surgeon and had performed the first liver transplant in humans. At that moment, I decided that's what I wanted to do. Later on, while I was still in high school, my parents arranged for me to shadow a couple of physicians they knew who were family friends who happened to be Black. My parents’ internist was Black. Ironically, my pediatrician, dermatologist, and orthodontist were white. I don’t believe that race had anything to do with those choices, just their availability and reputations.

Although this was Greensboro in the mid to late '70s, as a kid I never really thought about race and medicine until I later learned that the surgeon I shadowed was one of the plaintiffs in the landmark civil rights case that led to the desegregation of hospitals in the South, Dr. Alvin Blount. Let me be clear, I was very aware of discrimination in general by race at that time. My parents played Dr. Martin Luther King speeches on our record player all the time. I walked a picket line with them at a local grocery store located in a neighborhood of color that employed no one of color in management. But, as a high schooler, I was too young and naïve to know the implications of race on healthcare.

Q: Can you describe how lack of racial diversity in healthcare, and surgery specifically, has impacted your experience as a person and as a professional?

It was early in my medical career that I discovered the lack of racial diversity in healthcare. There were five African Americans in my Duke Medical School class of 100. Of course, at that time there were fewer attendings and residents across the board who looked like me. I was the second African American resident to finish Duke's General Surgery Residency Program; there were few physician role models around who shared my experience. Dr. Onye Akwari, our first Black surgeon on the faculty at Duke, was a source of pride for me when I was a resident. He was so dignified, so intelligent, so distinguished. Years later, Dr. Jim Douglas joined the Division of Cardiothoracic Surgery. I remember scrubbing in on an open heart operation with him. The surgeon was Black, as was the perfusionist, the scrub nurse, and both residents. We quietly joked, ‘If only this patient could see his team.’ We were sure that we made Duke history that day.

When I first entered transplantation, there were fewer than 15 Black transplant surgeons in the United States. That number did not scare me, but it did make me realize that I owed it to my community to talk about disease processes leading to transplantation that affect people of color disproportionately. I have spent many Sundays in Black churches, and many other days at HBCU's [historically Black colleges and universities] and high schools, speaking about diabetes, hypertension, hepatitis, and organ transplantation.

Q: People from different generations sometimes have vastly different life experiences. Could you describe how your experience might compare to younger generations of people of color?

There are some commonalties experienced by people of color, but the experience is not monolithic. I would argue that if I had a twin sister with identical career goals, her experience would have been much harder than mine. Women in surgery, no matter their race or ethnicity, have had it harder than me. People of color have always known that there is a lack of diversity at the table. The awareness of this lack of diversity by those in power has grown over the years. Being the first of anything brings its own unique challenges—Jackie Robinson and Barack Obama come to mind. There are fewer firsts that this generation will have to face, but the sequelae of systemic racism still make it hard to get to the table.

As with everyone else, COVID-19 has affected all facets of my life: the empty nest is now full again with college students, and the manner that I interact with patients has changed dramatically. I'm a hand shaker–hugger type of physician. I love to celebrate with my patients. The pandemic has changed those interactions dramatically.

Q: This year has been a difficult one, first with COVID-19 and then with the spotlight on the pandemic of racism in our country. Could you describe your experience this year?

I feel sorry for the parents of elementary school children trying to teach at home for the first time, and for college students who are missing out on the best years of their lives. COVID-19 has ravaged communities of color, and I am just the demographic who would be predicted to do poorly with the disease.

I have had a lifetime awareness of racism. What is different about this year is that I've been asked to share my experiences. The toughest story I told was that of my son being stopped while driving by police officers in our liberal Chapel Hill neighborhood, within a stone's throw of our house, when he was a senior in high school. Two patrol cars, multiple officers, unlocking their holsters. We thank God that we had given him 'the talk' years earlier. On another occasion, our neighbor across the street called the police on him because he looked suspicious—at his own house. My wife and I went over and introduced ourselves when they first moved in. We regret that we didn't take our son with us.

Q: What can Duke do to continue moving us forward in a positive direction?

It's obvious that Duke is taking systemic racism, diversity, and inclusion seriously given the number of initiatives that have been launched. It feels different this time. The murder of George Floyd hit a nerve. People are starting to realize that the murders of Botham Jean, who was killed in his own apartment by an off-duty officer, Breonna Taylor, Philando Castile, and countless others have a sinister etiology rooted in systemic racism. Fixing the problem requires acknowledging the problem. I think we are now beginning to explore the acknowledgement phase.

Give to Duke Surgery

A gift to the Department of Surgery is a gift of knowledge, discovery, and life.