With a buzzing phone and dinging inbox repeatedly begging for her attention, Dr. Georgia Beasley momentarily tunes out the chaos to discuss the journey that led to her current position at Duke. Here, she splits her time between treating melanoma patients in the clinic and researching novel treatments for the disease in the laboratory.

“When looking at other major centers, I saw that most of their surgeons only focused on operating,” she says. “I knew doing that wouldn’t make me the happiest. In studying cancer, everything is moving toward immune-based approaches. If I wanted to stay in surgery, especially in treating melanoma, I needed to start researching more about immunology.”

Stories of surgeon–scientists like this one are becoming the exception. For many surgeons, time constraints, lack of funding, and pressure to increase patient volume have restricted research time to the lab years of medical training. A 2017 survey in Annals of Surgery revealed that only 32% of surgeons believed it was possible to be successful in basic science in today’s working environment. And so she did. Now an Assistant Professor of Surgery at Duke, Dr. Beasley reconnected with the group that first introduced her to medicine 20 years ago. The team recently broke ground in using a mutated poliovirus as a therapy for recurrent glioblastoma. By triggering an immune response, the therapy causes the body to wage war on the brain tumor in the same way it would another virus. For the last year, Dr. Beasley has been testing the use of this treatment for melanoma, and she is almost ready to begin the therapy with patients.

Department Chair Allan D. Kirk, MD, PhD, believes this mindset to be detrimental to patient care. Due to surgeons’ close proximity to disease, they are uniquely positioned to make lasting contributions to scientific discovery through experiential expertise, which in turn will lead to improved patient care. As such, Duke is working on solutions to find equilibrium—to create a balanced system that supports its surgeon–scientists in finding success in both fields.

Opposing Forces: Clinic vs. Laboratory

As a surgeon–scientist in the Division of Plastic, Maxillofacial, and Oral Surgery, David Brown, MD, PhD, splits his time between navigating the figurative waters of establishing his clinical practice in regenerative medicine and wound healing, and researching in the literal waters of the Poss Lab, where he uses live imaging to study the genetic model system of zebrafish.

“Being a surgeon–scientist is a notoriously difficult career path,” Dr. Brown says. “We have to try to excel on both fronts, but especially trying to get our lab and research up and running while we are also establishing our clinical practice. It can be a pretty daunting task.”

Dr. Brown isn’t the only one feeling this pressure. The NIH confirmed through a 2014 workforce that physician–scientists are often pulled by opposing forces: one, a commitment to providing excellent clinical care, and another, a dedication to research and scientific discovery. Surgery and research—two fields that have historically worked harmoniously to cure and prevent disease—are becoming mutually exclusive. In essence, the system is now an unbalanced equation.

Four years after the NIH’s physician–scientist report, efforts to create balance are beginning to unfold. The NIH-funded Stimulating Access to Research during Residency (StARR) R38 award supports resident–investigators on a research track over a 5-year period, and seeks to curtail the increasing numbers of physicians asked to support more of their income through clinical practice.

The NIH released ten StARR awards in 2018, with two of them awarded to Duke. Dr. David Harpole, Professor of Cardiovascular and Thoracic Surgery, is a principal investigator of a mentor team

for one award, an $884,000 grant from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. He is enthusiastic that the grant will foster a successful research environment for residents.

“If you look at the advances in medicine in the last 30 years, it has mostly all been based on research supported by NIH and pharmaceuticals,” Dr. Harpole says. “If we don’t have people strengthened in medical research, we will no longer be at the forefront of innovation. Getting people who are active in surgery research doesn’t mean they are writing grants, and the R38 award will help to increase that.”

Balancing the Equation

The StARR awards are a part of a broader initiative in Duke’s School of Medicine to support physician–scientists, a cause Dean Mary E. Klotman fully stands behind. In addition to seeking out funding opportunities, a new Office for Physician–Scientist Development is in the works, with a goal to recruit and mentor clinicians who wish to continue research.

“Duke’s receipt of these important awards and establishment of this new office will catapult our ongoing efforts to encourage and help develop more physician–scientists, the number of which has been steadily decreasing,” says Dean Klotman. “Physician–scientists bring a knowledge of both laboratory and clinical research that is essential for translating discovery.”

In order to cultivate a system of support for its scientists within the department, Duke Surgery first needs a faculty with a strong penchant for research, a quality high on the list in recent recruiting efforts.

Forming Stronger Bonds

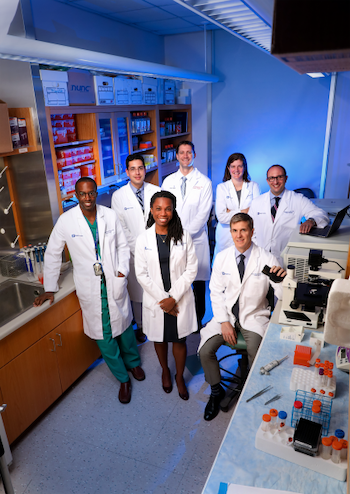

While recruiting research-oriented faculty is important, providing support for new and existing surgeon–scientists in our department is integral to their success. To do so, the department has formed a small cohort of faculty across multiple specialties, a collaboration that allows its members to share ideas, give feedback, and support one another as they balance the equally demanding roles of surgeon and scientist.

As part of the cohort, junior faculty will work with mentors who have excelled in research, including Vice Chair of Research and Professor of Surgery Shelley Hwang, MD, MPH.

“Duke's surgeon–scientists are essential to moving our field into the future,” Dr. Hwang says. “One of our key missions is to guide and support them with the clear intent of ensuring their success. I am proud to be in one of the few surgery departments in the country that prioritizes growing this critical pipeline.“

As a member of the cohort, abdominal transplant surgeon Andrew Barbas, MD, says bringing together faculty from both sides of the fence is a rare opportunity. “Dr. Kirk and Dr. Hwang have long distinguished careers in clinical work and laboratory-based investigation,” he says. “We all work in different areas, but there are some common themes, tools, and techniques that might be helpful across disciplines. That exposure is helpful.”

Even for non-traditional scientists, the cohort provides meaningful support. Assistant Professor of Surgery Oluwadamilola Fayanju, MD, MA, MPHS, works in health services to reduce disparities in breast cancer care, but her focus on big data analysis to improve care requires a great deal of research time outside of the clinic. She is grateful to be part of a department that allows her to pursue these interests passionately.

“I’m excited to be at Duke because of the many research resources that exist here,” Dr. Fayanju says. “We have great mentorship in Dr. Kirk and Dr. Shelley Hwang, and now Dr. Peter Allen joining us as the chief of Surgical Oncology. These are world-renowned researchers, and having leadership that is so strongly aligned with the scientific mission makes it easier for us younger faculty to pursue that, and to be passionate about it. We can focus on furthering the scientific fields that we are in, while also providing excellent care to our patients.”

Falling into Place

During their first meeting in July 2018, Dr. Kirk’s initial talk included a comedic metaphor about the role of a surgeon–scientist, but one that resonated with Dr. Brown. “Being a surgeon–scientist is a lot like playing a game of Tetris,” he recalls from Dr. Kirk’s message. “All of the pieces have to fit together. You have to rotate them into position, and you can’t stop them from dropping no matter what. If you don’t get it all just right, your work continues to build up. As you progress, things get harder, not easier, and everything comes at you faster. The reward for playing the game—it’s that you get to keep playing.”

For our successful surgeon–scientists—those who have found the balance between exceptional care for patients today, and research that will help innumerable patients tomorrow—that reward is enough to keep playing the game.