Bringing Smiles Back: Facial Reanimation Surgery at Duke

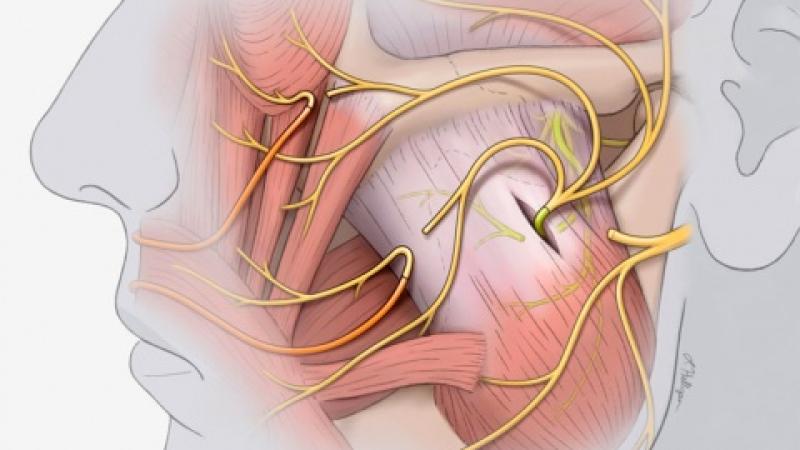

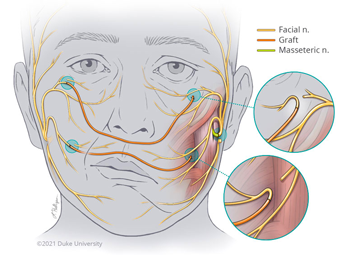

Image above: Branches of the impaired facial nerve are reconnected to the masseteric nerve and to cross-facial grafts to restore functionality. Illustration by Lauren Halligan, CMI, Section of Surgical Disciplines.

People connect to the world by their facial expressions. The ability to express emotions through a smile is a uniquely human response that evolved to enhance social interaction and connectedness. A smile can show a myriad of emotions from happiness to love that bond friends, family, and even strangers together.

Individuals who experience facial paralysis have difficulty expressing their emotions through their face because they are unable to move their mouth, eyelids, or forehead due to congenital conditions or acquired causes, including cancer, trauma, and infectious disease.

Assistant Professor of Surgery, Division of Plastic, Maxillofacial, and Oral Surgery

"Lack of facial nerve function, for whatever cause, reduces or entirely eliminates facial expression on the affected side of the face," says Brett T. Phillips, MD, MBA, Assistant Professor of Surgery, Division of Plastic, Maxillofacial, and Oral Surgery. "These patients cannot raise their eyebrows or close their eyes. They cannot smile or frown. To those unfamiliar with the disorder, it may resemble or be mistaken as a stroke."

In addition to a lack of facial expression, patients with facial paralysis may encounter functional consequences that significantly impact their quality of life. Eating and drinking become challenging because they are unable to close their mouths, which may also lead to dental issues. Patients may endure significant eye problems, including pain and even blindness, due to the inability to blink or close their eyes.

Professor and Chief,

Division of Plastic,

Maxillofacial, and

Oral Surgery

The facial paralysis program at Duke was created in 2002 by Jeffrey R. Marcus, MD, Professor and Chief, Division of Plastic, Maxillofacial, and Oral Surgery, who had just arrived at Duke from training at the pioneering facial nerve center at the University of Toronto Hospital for Sick Children. Dr. Marcus and Dr. Phillips treat both adult and pediatric patients with facial paralysis. In adults, Dr. Phillips says the most common cases of facial paralysis they see result from resection of brain tumors, such as acoustic neuromas, and Bell’s palsy, a sudden, temporary weakness of the muscles on one side of the face. In children, the team cares for patients with congenital facial paralysis. These patients are born without a functional facial nerve, such as in Moebius syndrome where the facial nerve is missing on both sides of the face.

"The causes of facial paralysis in children are different than adults," explains Dr. Marcus. "Bell’s palsy is less common. Congenital absence of the nerve is a rare condition, but more common for our team as a referral center for the condition. In addition, the recognition of the Duke Brain Tumor Center has brought a number of patients with brainstem-level tumors who have undergone life-saving successful treatment, but who occasionally have involvement of the facial nerve and lose function."

The goal of facial reanimation is to provide both nerve and muscle function while enhancing the symmetry of the face. Conceptually, treatment falls into two main strategies: restore or replace. For those who initially have normal function, but who suffer injury or loss of function, surgery can restore movement by transferring or connecting working nerves to the paralyzed branches of the facial nerve. These procedures depend on early referral to restore stimulus to the facial muscles before they have time to atrophy and become non-functional.

For those with congenital or long-standing paralysis in which the normal facial muscles are not available for reconnection, a separate type of sophisticated reanimation allows the surgeons to replace by transplanting a muscle from elsewhere in the body to mimic the function of the facial muscles, particularly for smiling. The type of surgery depends on the nature and duration of the injury.

"Nerve grafting or nerve transfer is performed to connect working (nearby and related) nerves to the paralyzed nerves to give the muscles they control the stimulus to contract," says Dr. Phillips. "Those could be normal nerves from the non-affected side of their face that control the very same movements. Or it could be a different nerve on the paralyzed side that can be transferred to control the desired movement. One common example is use of the masseteric nerve, which is normally in partial control of biting down, to the non-working facial nerve branches intended for creating a smile. In these cases, the transferred or grafted nerves provide the power to get the facial muscles working again."

When the facial muscles are not present from birth or have atrophied over time following injury, they must be replaced by new muscle to allow the patient to have expressions. The new muscle comes from elsewhere on the body; it must be transplanted along with its functioning nerves and blood vessels, which are connected to corresponding nerves and vessels in the face. Given the long-standing history of Duke Plastic Surgery in the field of reconstructive microsurgery, these cases leverage the capabilities of the team.

"In free muscle transfer, we take a muscle from the inner aspect of the thigh that has a consistently present artery, vein, and nerve. We transfer the muscle to the face, and we connect the blood vessels so that it gets blood flow. Then, we connect the nerve to either a nerve graft coming across their face or to the masseter nerve. Either will allow for the innervation of the muscle and allow patients to smile."

- Dr. Brett T. Phillips, Assistant Professor of Surgery

The specific treatments vary depending on the cause and the time elapsed since loss of function. But one thing is common with all treatments—they all work better when they are aided by postoperative therapy, including strengthening and coordination. "Our team has been fortunate to have excellent therapists since our inception led over all these years by Lisa Massa, CLT, PT, WCS," says Dr. Marcus. "Over time, with physical therapy, biofeedback, mirror exercises, and practice by the patient, they can actually get very close to being spontaneous regardless of the type of reanimation they undergo."

Less invasive procedures, such as Botox® fillers, can mask the symptoms of facial paralysis but do not restore facial function. Dr. Phillips often performs masking procedures for patients with Bell’s palsy and Ramsay Hunt syndrome to provide symmetry.

"It's a combination of all these treatments: Botox® fillers, static procedures, cosmetic procedures, and then nerve grafting and free muscle transfer," says Dr. Phillips. "There's a whole spectrum of different treatments that can be offered to make patients as symmetrical and functional as possible."

The time until patients recover function varies according to the procedure. Dr. Phillips says it can take any where from 3–6 months for certain procedures and 1–2 years for other procedures like free muscle transfer to produce a normal expression.

"When you see the patient six months, nine months, or even a year later, and they walk into your office, and you say, 'Okay smile for me,' and they smile! It's one of the most amazing feelings that I have experienced as a surgeon at Duke," says Dr. Phillips. "In kids, it's super special to see their first smile. And in adults, it's a great feeling to share in this amazement."

Dr. Marcus says, "People often associate plastic surgery with a desire to have ideal beauty. Social media and public perception play into this. But like many of the conditions we treat in children and adults, for some people, all they want is to just look like anyone else. Not to look better than everyone else. Just to fit in. We are really lucky to be able to do what we do in our work. It is extraordinarily gratifying."

Give to Duke Surgery

A gift to the Department of Surgery is a gift of knowledge, discovery, and life.